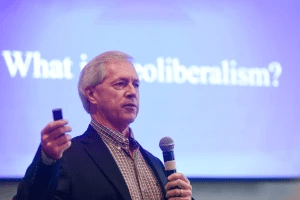

Three years ago, we interviewed Dr. Bruce Rogers-Vaughn (above), an ordained Baptist minister, pastoral psychotherapist and Associate Professor of the Practice of Pastoral Theology and Counseling at Vanderbilt Divinity School, and the author of Caring for Souls in a Neoliberal Age (Palgrave, 2016). “Neoliberalism,” he writes, “has become so encompassing and powerful that it is now the most significant factor in shaping how, why, and to what degree human beings suffer.”

This is why Bruce presses for a “post-capitalist pastoral theology” that empowers people to resist the system (instead of adapt to it), to embrace communion and wholeness in relation to others and the earth (instead of functioning in accord with the values of production and consumption) and to pursue interdependent reliance within the web of human relationships (instead of accepting shame-based personal responsibility narratives).

Above all, Bruce prods pastors, therapists and social workers to identify the source of personal distress in the social and political environment instead of within the individual (he rejects what he calls “sophisticated exercises in blaming the victim”). Oh—one more thing about Bruce. All of his work is informed by his deep roots in southern Appalachia.

This is an excerpt from the beginning of our five-part conversation. See this for Part I, this for Part II, this for Part III and this for Part IV.

—————————————————————————————-

Neoliberalism is simply an awful word. It is almost inevitably misleading. When I first encountered this expression, I imagined it was designating some new (“neo-”) form of political or theological “liberal.” But, actually, the term originates from economic philosophy. Its first proponents—the so-called “German Ordoliberals”—coined the name during the 1930s. Today the word is used, almost exclusively by its critics, to refer to the current phase of capitalism. This phase gained political traction in the USA and the UK in the 1980s, during the Reagan and Thatcher administrations, and by the mid-1990s was the dominant way of thinking and believing that guided global economics, politics, and culture.

Let me pause right there. To say that neoliberalism is “the current phase of capitalism” is to acknowledge that it is—first and fundamentally—capitalism. Its main features are continuous with the capitalism that first emerged in England during the seventeenth century, fueled colonial expansion (including the slave trade) and, later, the Industrial Revolution. I am a Christian minister and theologian. Your website advocates “radical discipleship” for today’s Christians. We must first recognize that capitalism and the heart of Christianity are incompatible, even adversarial. The word capital simply means “money,” or wealth, and the suffix “-ism” identifies capitalism as a system—a system composed of subsystems, really—that strives to place money at the center of all human life. So, capitalism is “moneyism.”

Jesus, according to the Gospels, said: “You cannot serve God and money.” Full stop. Most Christians alive today have inherited an imperialist and triumphant version of Christianity that tries to get around this basic conflict. By using something like the Protestant Reformers’ “two realms doctrine,” we now assume that our faith concerns only our private lives, and is focused on what comes “after this life,” or, somewhat vaguely, on “the world to come.” This leads even those Christians who think of themselves as progressive to comply with capitalism, which we imagine is left to govern “the present realm,” including all political and economic life. “A system that puts profits at the center of life may be bad,” we think to ourselves, “but what can we do? It’s just the way the world is.”

This attitude is also contrary to the life and message of Jesus as portrayed in the Gospels, and it nullifies our Christian witness and calling. Almost every minute, somewhere in the world, Christians are praying the Lord’s Prayer. The initial invocation ends with: “… Thy will be done, on earth, as it is in heaven.” Even the notion of “eternal life,” in the New Testament, does not simply refer to “the afterlife,” but to a quality of life that is already sprouting and spreading in this life—both individual and corporate. Then, in the middle of the Lord’s Prayer, we pray these words: “And forgive us our debts, as we forgive our debtors.” There you have it—economics is at the heart of the prayer that summarized Jesus’ teachings and actions. If this one intercession was fulfilled, it would be the end of today’s capitalism, a system in which all money is created as debt. We cannot abide capitalism. Not because we are “Marxists” or “socialists” or “communists” (scare words which few people understand), but because we are Christians (which is, I fear, another word we may not understand).

I go so far as to say that capitalism is a type of religion. It is a faith system that is actively rooting out and destroying the ancient religions, or is otherwise reinterpreting them to conform to its own beliefs and practices (a perhaps more malignant sort of destruction). This is not a new idea. As early as 1921, the Jewish political philosopher Walter Benjamin wrote an unfinished essay titled “Capitalism as a Religion.” Paul Tillich, arguably the most recognized theologian of the twentieth century, regarded capitalism as a “quasi-religion” that displayed an essentially demonic character. Tillich was not alone among theologians in his assessment. Karen Vaughn, an economist, has observed: “It is difficult to think of a major Christian theologian who wrote from 1920 through 1960 who regarded capitalism with favor.” After that time, with a handful of recent exceptions, the criticism of capitalism among Christian theologians has almost disappeared. This is one indication, I believe, of the power neoliberalism has had in suppressing opposing voices since the 1980s. Again, it is time for Christians and theologians to get back to their roots. (And let’s remember: getting to “the root” of something is the meaning behind the word “radical.)