A poem from Drew Jackson. #RalphYarl

A poem from Drew Jackson. #RalphYarl

An excerpt from the Combahee River Collective (1977).

Above all else, Our politics initially sprang from the shared belief that Black women are inherently valuable, that our liberation is a necessity not as an adjunct to somebody else’s may because of our need as human persons for autonomy. This may seem so obvious as to sound simplistic, but it is apparent that no other ostensibly progressive movement has ever considered our specific oppression as a priority or worked seriously for the ending of that oppression. Merely naming the pejorative stereotypes attributed to Black women (e.g. mammy, matriarch, Sapphire, whore, bulldagger), let alone cataloguing the cruel, often murderous, treatment we receive, indicates how little value has been placed upon our lives during four centuries of bondage in the Western hemisphere. We realize that the only people who care enough about us to work consistently for our liberation are us. Our politics evolve from a healthy love for ourselves, our sisters and our community which allows us to continue our struggle and work.

This focusing upon our own oppression is embodied in the concept of identity politics. We believe that the most profound and potentially most radical politics come directly out of our own identity, as opposed to working to end somebody else’s oppression. In the case of Black women this is a particularly repugnant, dangerous, threatening, and therefore revolutionary concept because it is obvious from looking at all the political movements that have preceded us that anyone is more worthy of liberation than ourselves. We reject pedestals, queenhood, and walking ten paces behind. To be recognized as human, levelly human, is enough.

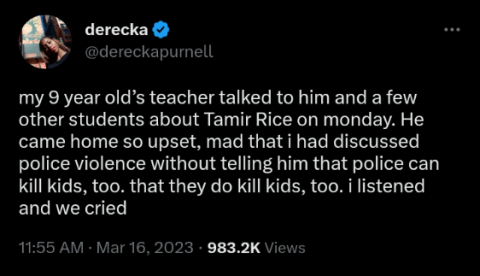

Continue reading “The Liberation of All Oppressed People”A Twitter thread from Derecka Purnell, a lawyer, community organizer and author of Becoming Abolitionists (2022)

From author and activist Rebecca Solnit, re-posted from social media.

Memo to my fellow white people ostentatiously complaining about how they didn’t like Everything Everywhere All At Once. I loved the film but if I didn’t I’d be aware how meaningful it is to other people–notably Asian and Asian American viewers– and not dump on their joy. It’s a huge breakthrough film in a white-dominated industry, and some of you are sounding pretty….checked-out…in your grousing.

[There are lots of other works of art where it’s very clear how meaningful it is to someone else, often because they have long gone unrepresented and overlooked, and if it’s not resonating the same way for me, it’s my goal to be attuned to why it resonates for them, not foreground my grumpy limitations and my luxury of already having films/ music/ stories/ songs enough about people like me. But there’s also always the question of why something doesn’t resonate. Can you not identify with characters of another race/sexual orientation/background or enjoy spending time watching their lives unfold? If not, you might want to explore that. A lot of young and queer people also loved the film. I’m not saying everyone must like it; but I am saying that thinking about the why or why not could be useful and also that a lot of the complaining sounds pretty close-minded and mean-spirited and very middle-aged. Black journalist Eugene Robinson wrote today: “That is a level of Asian representation we have never seen before at the Oscars. In the past, the message from Hollywood to Asian actors and creators has ranged from, effectively, “squeeze yourself into this stereotyped pigeonhole” to “just stay the hell away.”’]

By Rev. Graylan Scott Hagler

“O say can you see,” stood in the place where God should be, and it didn’t wave but passively stood, planted, and seemingly unmovable across from the Christian flag, that is also red, white and blue. This is the scene in so many Christian houses of worship across the country. It serves as a reminder to the congregants that they are not only in America, but quietly and effectively offers the assertion that America is a Christian country, founded on Christian principles, and in order to be a good American necessitates being a Christian. Or, in the synagogue, on the Bimah, often stands two flags, an American one and the Star of David, that confirms not only American loyalty, but loyalty to another country, and to another political ideology. These symbols are not too subtle, and the implied message is God and country, and country or countries on the same level as God.

According to the theologies of the Judeo-Christian traditions there is no god greater than God, and there is this timeless struggle against idol worship in all its manifestations. We caution against worshipping money and riches, against pride and arrogance, we call for humility and the extension of love to our neighbors down the street and across the globe. We pray to keep God before us and above us, and seek to be accountable to that God. We strive to create a synthesis between our daily living and our worship, and seek to allow nothing to supplant the prominence of God in our lives. Yet, on these altars, these places that are set high and represents the loftiness and sacredness of God, stands symbols of nationalistic pride. They are placed in the place where the spirit and concept of God should reside, and we are therefore declaring that God must share sacred space with nationalistic symbols of pride, arrogance and militarism. Some would suggest that this is simply patriotism, but patriotism placed on the altar alongside the conceptional sacredness of God is the height of idolatry, and in Christian text we are taught,

Continue reading “God’s Competition with Race, Gender and Nationalism”

It’s March. On this site, that means that Black History month is just starting. This is an excerpt from Bettina Love’s We Want to do More than Survive: Abolitionist Teaching and the Pursuit of Educational Freedom (2019).

Antidarkness is the social disregard for dark bodies and the denial of dark people’s existence and humanity. When White students attend nearly all-White schools, intentionally removed from America’s darkness to reinforce White dominance, that is antidarkness. When dark people are present in school curriculums as unfortunate circumstances of history, that is antidarkness. When schools are filled with White faces in positions of authority and dark faces in the school’s help staff, that is antidarkness. The idea that dark people have had no impact on history or the progress of mankind is one of the foundational ideas of White supremacy. Denying dark people’s existence and contributions to human progress relegates dark folx to being takers and not cocreators of history or their lives…

…What is astonishing is that through all the suffering the dark body endures, there is joy, Black joy. I do not mean the type of fabricated and forced joy found in a Pepsi commercial. I am talking about joy that originates in resistance, joy that is discovered in making a way out of no way, joy that is uncovered when you know how to love yourself and others, joy that comes from relieving pain, joy that is generated in music and art that puts words and/or images to your life’s greatest challenges and pleasures and joy in teaching from a place of resistance, agitation, purpose, justice, love and mattering.

A PSA from Brendon Woods, the chief public defender of Alameda County.

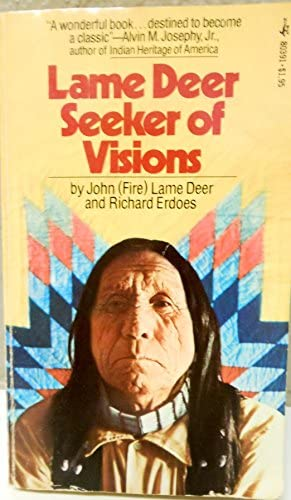

From John (Fire) Lame Deer, Sioux Lakota (1903-1976). Thanks to Lorna Standingready for posting.

“Before our white brothers arrived to make us civilized men,

we didn’t have any kind of prison. Because of this, we had no delinquents.

Without a prison, there can be no delinquents.

We had no locks nor keys and therefore among us there were no thieves.

When someone was so poor that he couldn’t afford a horse, a tent or a blanket,

he would, in that case, receive it all as a gift.

We were too uncivilized to give great importance to private property.

We didn’t know any kind of money and consequently, the value of a human being

was not determined by his wealth.

We had no written laws laid down, no lawyers, no politicians,

therefore we were not able to cheat and swindle one another.

We were really in bad shape before the white men arrived and I don’t know

how to explain how we were able to manage without these fundamental things

that (so they tell us) are so necessary for a civilized society.”

It’s Black History Month, something we celebrate all year long at RadicalDiscipleship.net. This is from the conclusion of bell hooks’ classic essay “Killing Rage” (1995).

Rage can be consuming. It must be tempered by an engagement with a full range of emotional responses to black struggle for self-determination. In mid-life, I see in myself that same rage at injustice which surfaced in me more than twenty years ago as I read the Autobiography of Malcolm X and experienced the world around me anew. Many of my peers seem to feel no rage or believe it has no place. They see themselves as estranged from angry black youth. Sharing rage connects those of us who are older and more experienced with younger black and non-black folks who are seeking ways to be self-actualized, self-determined, who are eager to participate in anti-racist struggle. Renewed, organized black liberation struggle cannot happen if we remain unable to tap collective black rage. Progressive black activists must show how we take that rage and move it beyond fruitless scapegoating of any group, linking it instead to a passion for freedom and justice that illuminates, heals, and makes redemptive struggle possible.