By Tommy Airey

By Tommy Airey

Way back in the wide-open fields of the Clinton years, the seed of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King was planted in me during a semester with Professor Bill Tuttle at the University of Kansas. Way back then, I was attending Campus Crusade bible study on Wednesdays, drinking a 12-pack of beer on Fridays and going to an all-white Evangelical church on Sundays. My spiritual life was a complete circus. Way back then, I struggled to make the simple connection that Dr. King was a Christian and that his perspective on Jesus was completely different than what my white Evangelical mentors and heroes were pitching.

At some point though, in that blessed window of opportunity between 9/11 and Hurricane Katrina, as drones and status updates and subprime mortgages burst into our world, Dr. King started coming through loud and clear. I got the message. Slowly. It fermented through friends and books and students and travel. This miraculous process pounded my heart with the real, subversive love of Jesus—a life-affirming force that strategized around what Dr. King called “understanding, creative, redemptive goodwill” for all. Meanwhile, as American armed forces invaded Muslim-majority countries, the economy grew and gas prices fell.

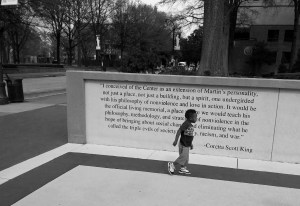

Last week, I took a post-Lenten pilgrimage to Atlanta for the 50th anniversary of King’s brutal murder. On April 4, I left Southeast Michigan in a whirlwind of snow flurries. Appropriately, I drove down Rosa Parks Highway into Ohio. Soon after the Montgomery Bus Boycott ended, Parks moved north to Detroit to flee Jim Crow. As it turns out, her subversive sit-down had severe consequences: she and her husband lost their jobs and endured constant death threats (these continued up north).

The last time Rosa Parks saw Martin King was at a speech and rally in suburban Gross Pointe, just east of Detroit. It was three weeks before his murder. King addressed a jam-packed high school gym and was repeatedly interrupted by white protestors. King was characteristically patient. He listened. But he didn’t hold back from telling the truth. He lamented that “large segments of white society are more concerned about tranquility and the status quo than about justice and humanity.” As King’s daughter, Bernice, says, her father was not afraid to chew up the meat and spit out the bones.

As I drove further south, the lavender-lined interstate harkened the budding of Spring, but billboards like the one advertising the upcoming Amy Grant concert turned back the clock. The same day I hightailed it through Tennessee humming “El Shaddai,” a resolution condemning neo-Nazis and white nationalists died in that state’s legislature. It called for the law-making body to “strongly denounce and oppose the totalitarian impulses, violent terrorism, xenophobic biases, and bigoted ideologies that are promoted by white nationalists and neo-Nazis.”

Contemporary Christian Music and overt white supremacy aren’t the only principalities that refuse to die. The real pain and suffering are inflicted by stubborn structural issues that come with a predictable disclaimer in suburbia: But that doesn’t have anything to do with race. Bulging prisons. Substandard housing. Houselessness. Joblessness. Pathetic wages. Police brutality. Slashed education. Inaccessibility to nutritious food and clean water. Bottom-of-the barrel healthcare. The privatization of the commons. Toxins spewing into neighborhoods.

The silence of my Spring drive beckoned my mind back to the Fall. The $800 million Little Caesar’s Arena opened in downtown Detroit to the fanfare of seven sold-out Kid Rock concerts. The racism went far beyond the confederate flags and white nationalist biker gangs stalking Woodward Avenue on opening night. White supremacy wears a well-tailored suit too. A coalition of corporate and government leaders keep on making decisions that devastate: the arena was financed with hundreds of millions of taxpayer money while tens of thousands of low-income Black Detroiters somehow survive in homes without running water. These suits increase rates and mandate shutoffs in the name of “changing the culture.” To add insult to injury, these suits commandeered hundreds of millions of dollars of federal TARP money allocated to help residents stay in their homes and transferred it to fund “blight removal.” Suburban contractors and developers were rewarded handsomely.

The King Center in Atlanta commemorated the 50th anniversary with a Beloved Community Talks Symposium to address King’s giant triplets of racism, militarism and poverty. Rev. Dr. Bernice King welcomed the small gathering by thanking the Black Lives Matter movement for confronting the last vestiges of racism. Dr. john a. powell, the Director of the Haas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society, defined whiteness as a concept of dominance and separation. It wants to get rid of race, but not get rid of racism. A tweet from Bryan Stevenson was proclaimed from the stage and echoed over meals together: “I believe that the opposite of poverty is justice.”

On a panel that equated poverty with violence, Rev. Liz Theoharis, the co-chair of the Poor People’s Campaign, exhorted the gathering to raise awareness by shifting the narrative away from Stormy Daniels to the real heroes and heroines struggling against poverty and homelessness all over the continent. Theoharis was asked about what Jesus really meant when he told his disciples that “the poor will always be with you,” a text she dedicated an entire book project to. Jesus was actually quoting from the Hebrew Bible. Deuteronomy 15. Theoharis called it the most radical passage in Scripture. God lays it out for the wilderness-wandering Israelites: if you forgive debts, release slaves, pay people a living wage and loan money without the expectation of repayment, then there will be prosperity for all. This is the biblical logic at the heart of a much-needed renewal movement.

Ultimately, as Martin wrote to Coretta back in the early 1950s, adherents of belovedness must cultivate an imagination that extends beyond traditional capitalism, a system that incentivizes hoarding mentalities. A narrative of mutual beneficiality is needed—what Dr. King called “the interrelated structure of reality.” The United States was, and continues to be, built on what my mentor Dr. Lily Mendoza calls “the undeniable debris of dead bodies, stolen wealth, and the enslavement of other beings, both human and non-human.”

The two-day symposium sustained a deeply spiritual focus throughout. Dr. Bernice King kept it real from the stage, sharing her own struggle with bitterness and resentment towards white folks in early adulthood. This hatred became a burden too great to bear, manifesting in physical ailments that plagued her. Eventually, she embraced the nonviolence of her parents. A key was her father’s focus on the crucial difference between like and love. Thankfully, we don’t have to like everyone. But love calls our name in every relationship and circumstance.

Marian Wright Edelman concluded with an upbeat keynote reflection. “We honor Dr. King,” she prodded, “by finishing the job.” She compared community organizers to fleas who, when they bite together, can make even the biggest dog uncomfortable. Edelman called for awareness-raising, steadfast strategizing, creativity, prayer and a commitment to repudiate the slogans of the opposition without repudiating the people.

Where do we go from here? Ironically, coming from a conference honoring a man, our struggles for justice, both historic and contemporary, keep calling people of faith and conscience to follow women, especially women of color. Bernice King proclaimed that if not for the role of women in Montgomery, the boycott would have lasted no more than two hours. She also reminded us that her mother publicly spoke out against the Vietnam War two full years before her dad famously did in 1967. Powell pointed to the success of the Doug Jones campaign where Black women organized and strategized a shocking victory in Alabama of all places.

Women of color, particularly Black women, are the empathic glue holding the suffering world together. They operate on a completely different wavelength than anything I ever experienced in the white Evangelical male-dominated landscape of my youth. They embody what Dr. King called “transphysics,” a spiritual dynamism originating deep in the gut, sparking a “fire that no one can put out.” I’m absolutely not proposing that we seek out more Black women to fill slots in a system bonded to racism, militarism and materialism. As King Center scholar-activist Sarah Thompson recently reminded me, “Decolonization is not the same thing as diversification.” The goal is liberation, not tokenization (or fetishization).

This is a proposal for apprenticeship, both personal and political, characterized by decentering what is white and male. When women of color are invisible or absent in spaces we traffic, it is always an opportunity to take inventory: what are the forces decentering them and driving them away? Women of color, filled with fierce truth-telling and tender compassion, are the underrated and overlooked Miriams who receive one verse of song for every eighteen that Moses is lavished after crossing the Red Sea. Yet, only these Miriams have the emotional and spiritual resources to lead us to the Promised Land. After all, in these days when everything is threatened, a two-hour boycott ain’t going to cut it.

Tommy, Nice bit of writing. Noted, I missed another memorable week in your life. Ta for the recap. Will enjoy the long version another time, face to face. Travel Safely, Clancy >