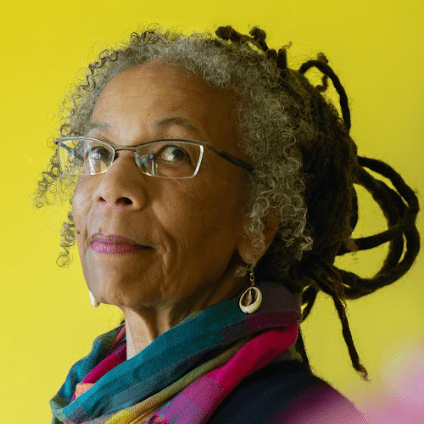

An excerpt from “How Much Discomfort is the Whole World Worth?” by Mariame Kaba and Kelly Hayes. Re-posted from Boston Review.

When people delve into activism, they often grapple with questions like, “Am I willing to get arrested?” when often the more pressing question for a new activist is, “Am I willing to listen, even when it’s hard?”

For organizer and scholar Ruth Wilson Gilmore (photo above), it was her time in Alcoholics Anonymous that helped her transform her practice of listening. “The main thing that I learned,” Gilmore told us, “especially in the first couple years that I was going to meetings, was the beauty of the rule against crosstalk. It was the best thing that ever happened to me, that I couldn’t say shit to anybody. I had to listen, and I had to learn to listen.” The urge to interject or object ran deep for Gilmore. “I’ve always been a nerd, yet I’ve always been a know-it-all,” she told us, “so there’s this tension between my nerdiness that wants to know everything and my know-it-all-ness that wants everybody to know that I know it all already.”

At first, listening did not come easily—or feel particularly productive—to Gilmore. “I would sit in these meetings, and I listened to people talk, and listened to them, and listened to them, and at first I was like, ‘I don’t get this, I don’t get this.’ And so for me in the early days, it was just a performance of words. I mean, my main thing was, ‘I won’t drink when I leave this meeting. I won’t drink, and I won’t use.’”

But over time, Gilmore began to appreciate the role of listening in the group’s collective struggle to avoid drugs and alcohol—even when she did not appreciate what was being said. “I would be getting more and more wound up, because there’d be the sexist guy going on about women and his wife, and then there’d be somebody else talking nonsense about whatever, [but I was] learning to just sit there, and listen, and keep my eye on the prize, which was not just that I wasn’t going to drink but that the only way I could not drink was if all of us didn’t drink.”

Being committed to the sobriety of every person in the room, which meant listening to their story and being invested in their well-being, helped Gilmore develop a deeper practice of patience. “That was kind of this transformation for me that carried into the organizing that I already used to do before I got sober,” she told us.

It is our ability to constructively engage with other people that will ultimately power our efforts. We have to nurture that ability and respect its importance in all of the ways that our society does not. And that skill of constructive engagement starts with listening.

Like so many other aspects of organizing, listening is a practice, and at times, it’s a strategic one.

We might need to hear something true that makes us uncomfortable. Listening deeply makes space for that to happen. But even if the person who’s talking is off base, we can often still learn by listening to them. Why do they feel the way they do? What sources informed or convinced them? What influences them? What strengthens their resolve? What makes them hesitant to get more involved or to engage more boldly? If you are in an organizing space together, how has that issue brought them into a shared space with you despite your differences? What points of agreement might you build upon? What is surprising about them? A good organizer wants to understand these things about the people around them, and you cannot truly understand these things about a person without listening.

Organizers will often repeat the maxim, “We have to meet people where they are at.” It is difficult to meet someone where they’re at when you do not know where they are. Until you have heard someone out, you do not know where they are, so how could you hope to meet them there? Relationships are not built through presumption or through the deployment of tropes or stereotypes. We must understand people as having their own unique experiences, traumas, struggles, ideas, and motivations that will inform how they show up to organizing spaces.

Some task-focused activists brush off activities that involve “talking about our feelings.” This is a common sentiment among bad listeners. The fundamental skill of patiently absorbing another person’s words in a respectful and thoughtful manner is desperately lacking in our society. For this reason, it is folly to expect this skill to manifest itself fully formed when it is most needed, such as in a heated meeting, if we are not building a greater culture of listening in our work.

A group culture that helps participants build their listening skills is an important component of successful organizing. Political education can create opportunities for people to practice listening to one another, without interruption, and interacting meaningfully with what others have contributed. For example, during the Great Depression, communist union organizers in Bessemer, Alabama, developed a practice of devoting thirty minutes of each meeting to political education. For thirty minutes, material would be read aloud—creating space to collectively listen while also allowing members who could not read the opportunity to hear the information. Members would then spend fifteen minutes discussing the material, listening to each other’s thoughts in response to the work.

In organizing, we sometimes expect people, including ourselves, to shed the habits this society has embedded in us through sheer force of will, when in reality we all need practice. Activities that help us hone our practice of listening can make us better organizers, improve our personal relationships, and help us build stronger and longer-lasting movements.

We are on the right track with our LIstening Parties!

I found this post extremely helpful to my organizing work.

Thanks.

<

div>Tina Schlabach

Sent from my iPhone

<

div dir=”ltr”>

<

blockquote type=”cite”>