By Ched Myers, a commentary on last Sunday’s Gospel

Today’s gospel text for the 23rd Sunday after Pentecost culminates Year C’s journey through Luke (next week’s “Reign of Christ Sunday” is a special feast day to close the liturgical year). It narrates the first half of the third gospel’s version of the “Synoptic Apocalypse” (Lk 21), which begins by portraying Jesus’ disciples, many of whom were up-country Galileans, as dazzled pilgrims encountering the grandeur of the “Holy” metropolis of Jerusalem for the first time (21:5).

Like rural folk visiting Washington DC for the first time, they were impressed (or perhaps just overwhelmed) by the imposing monuments and edifices of their nation, which conjured a visceral patriotism they assumed Jesus shared. We, too, inevitably experience moments of existential awe by our civilization, especially as powerfully represented by its built environment—whether civic, religious, industrial or military. We all dwell under the shadow cast by the self-congratulatory narrative of empire; it is so heroic and compelling that we become enamored with (or paralyzed by) the systems that rule over us, despite ourselves. “Wow!” they/we intone, “God bless America!”—then turn to Jesus to add plaintively, “right??”

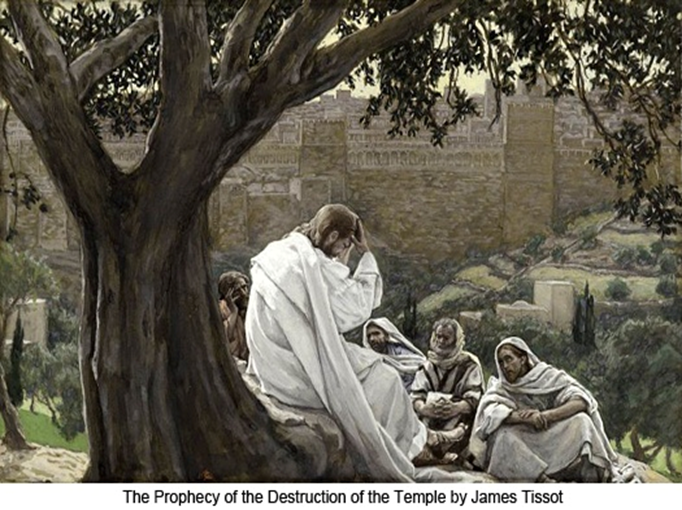

But to their/our horror, the Nazarene instead puts his head in his hands. (I’m generally not a fan of Gilded Age French Catholic Pietist painter James Tissot, but I rather like his depiction of this moment above). “Ah, yes… all this, all this…” he responds slowly, sadly, deliberatively, “…will be ‘overthrown’…” (the literal meaning of the Greek verb kataluo), “…stone by stone.”

Talk about deconstruction!

Not exactly a made-for-TV Christian nationalist moment. It is, of course, this very exclamation that will be used to convict Jesus of treason when he is brought before the authorities. Indeed, this rebuff understandably upsets all who can’t quite envision a world that does NOT dwell under the sacred canopy of empire. It only invokes anxieties about the end of our world, which is why here Jesus follows with an apocalyptic vision of history.

Elsewhere I’ve described this as follows:

Apocalyptic discourse in the Bible is not about predicting God’s cataclysmic destruction of the world, as so often assumed in popular culture. Rather it expresses the fierce imagination of those who long for the end of destructive oppression by the imperial state. After all, for the poor, the ‘end of the world’ is already and forever being visited upon their communities by soldiers and fortune hunters and police.

Apocalyptic as a literature of resistance arose in antiquity first during the era of Persian, then Hellenistic, then Roman domination of the Mediterranean world, regimes which brought profound changes to traditional lifeways. Powerful elites ruled ever more cruelly, extracted resources more deeply, imposed slavery more widely, and fought unending wars more mercilessly. All of this made life more miserable for peasants, as well as for outlying pastoral and Indigenous peoples caught in the vortex of expanding States.

The Greek word apocalypsis means ‘unmasking or unveiling.’ It has to do with a kind of vision that is able to see through the dominant stories of empire—the grand fictions of entitlement and sovereignty, militaristic triumphalism, seductive myths of grandeur, and severe orthodoxies of law and order. Apocalyptic seeks to lift what Morpheus, in the 1999 film The Matrix, describes as ‘the world that has been pulled over our eyes’: the propaganda of empire that masks the truth, distorts what it means to be human, and hijacks history. Apocalyptic, in contrast, seeks a ‘double unmasking,’ by:

- stripping away the layers of denial and delusion that keep us distracted, in order to expose realities of personal and political suffering and injustice—that is, to see the world as it really is from the perspective of the poor and victims of violence; and then

- transfusing our dulled and dumbed-down imaginations with visions of the world as it really could and should be from the perspective of divine love and justice. The possibilities of a different way of being are revealed, or at least glimpsed, in apocalyptic visions.”

So Luke’s final offering to our liturgical year is to throw us head-long into this radical imaginary. He also stipulates up front that no one in authority will receive it warmly (Lk 21:12). Which for disciples “opens up” the “opportunity to bear witness” (Gk marturion), though at a cost.

In the wake of this week’s mid-term election circus and Veteran’s Day pieties, today’s “good news” Word provides to those of us trying to make sense of the “signs of the times” some needed vision-correction.

Interesting post, keep it up!